23. Advanced material: Signature verification¶

23.1. Attribute shadowing¶

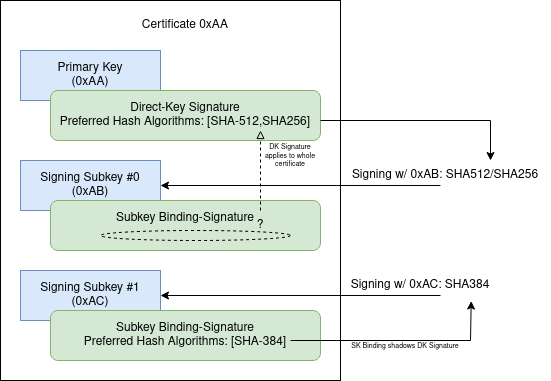

When determining the preferences of a key, several signatures may have to be inspected.

For example, when using a signing subkey to generate a data signature, an implementation might want to check for hash algorithm preferences on the subkey binding signature. However, the RFC states that signature subpackets in a direct key signature (which may also contain preferences) on the OpenPGP certificate’s primary key apply to the entire OpenPGP key, and therefore also to the signing subkey.

In this case, the implementation uses the preferences from the subkey binding signature, but if no such subpacket is found on the latest binding signature, it falls back to the preferences from the direct key signature. This is called attribute shadowing, since direct key signature subpackets apply to all subkeys, but are shadowed by binding signature subpackets.

Fig. 36 Inheritance and Shadowing of Attributes¶

Note

Attribute shadowing is relatively straightforward to reason about when used for algorithm preferences. For other subpacket types, shadowing may be confusing, and/or the semantics underspecified (e.g. for key expiration time subpackets).

23.2. Signature shadowing¶

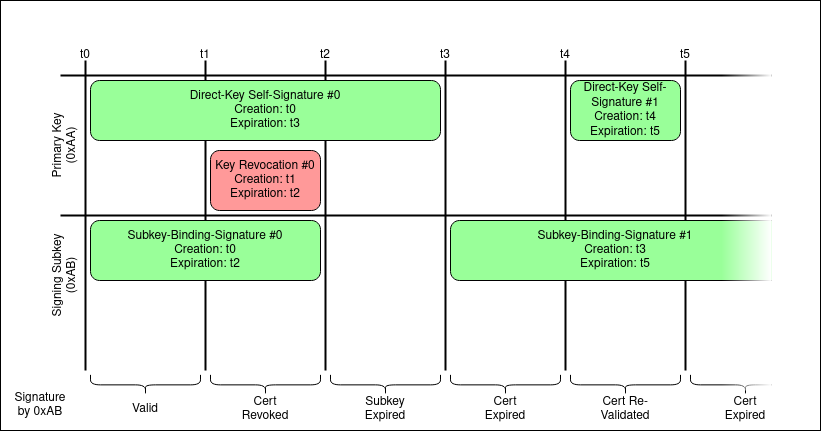

When inspecting signatures on a component of an OpenPGP certificate, of the signatures that are in effect for each function, only the newest is considered.

In other words:

If there are three binding signatures

A, B, Cfor a subkey,where:

Awas created att0,Batt1, andCatt3, witht0 < t1 < t2 < t3.

Then at

t2, an implementation only needs to consider signatureB,because

Cis not yet in effect, andAis shadowed, because it is older thanB.

Fig. 37 An example for how certificate validity can change with time.¶

Note

Signature shadowing should not be confused with attribute shadowing.

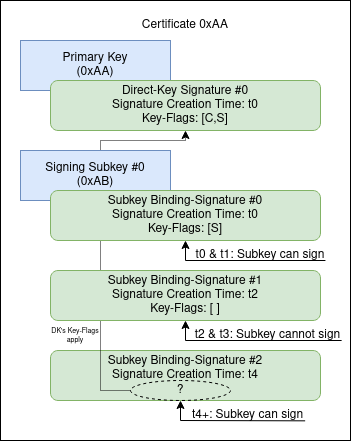

As attribute and signature shadowing can occur in combination, it is not always obvious which properties a key has at a given time.

Fig. 38 Signatures shadow one another, based on reference time.¶

23.3. Which signatures take precedence?¶

Multiple signatures can be attached to an OpenPGP certificate or component. These signatures can contain conflicting information.

When verifying a signature that is not self-qualifying, an implementation needs to inspect self-qualifying signatures in the issuer’s certificate for qualification. The certificate may contain multiple signatures for one component.

For example, there could be multiple subkey binding signatures for one subkey. This could be the case because the expiration time in the original binding signature has expired, and the certificate holder has issued a new binding signature with an extended expiration time.

In general, for each category of signatures (categories such as binding signatures for one particular subkey), the signature with the latest creation time takes precedence, and only that signature is considered.

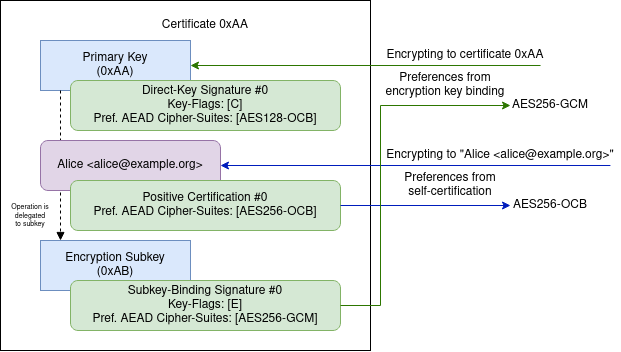

Alternatively, there can be competing qualifying signatures of different types, e.g., a direct key signature and a self-certification signature on a primary User ID. Both of these contain metadata associated with the entire certificate. By default, the direct key signature is preferred[1] in OpenPGP version 6.

Depending on how a certificate is “located,” different metadata from possible candidate signatures “shadow” one another. The RFC states that when a certificate is “located” by the OpenPGP software “via an identity”, then the metadata associated with that identity takes precedence over more global metadata, such as that associated with the certificate’s primary key, with a direct key signature.

For example, the latest direct key signature could list “SHA512, SHA384” as hash algorithm preferences, while the latest self-certification of the User ID “Bob” could list only “SHA256.” For yet another User ID “Bobby,” the self-signature could list no hash algorithm preferences at all. If the user wants to compose a signed message using the associated OpenPGP key they need to figure out which preferences to use.

The specification recommends that implementations decide which signature takes precedence by the way the certificate is “addressed.”

Fig. 39 Preferences are sourced from signatures on different components, depending on how the key is addressed.¶

If the user wants to write an email as “Bob,” it should consider the signature on “Bob,” so SHA256 should be used as hash algorithm. If instead the user wants to write as “Bobby,” the implementation should inspect the self-certification on “Bobby” instead. However, since this signature does not carry any hash algorithm preferences subpacket, the implementation must fall back to the direct key signature instead. The same is true if the certificate is used without any User ID as sender.

To complicate things further: Algorithm preferences can also be stated on subkey binding signatures, so if the certificate has a dedicated signing subkey, there is yet another signature which could take precedence. Preferences from the subkey binding signature take precedence over the direct key signature, but not over self-certifications on the User ID.

There can be more than one signature on a component. As an example, there are 3 direct key signatures (e.g., because the key’s expiry has been extended two times). In general, for each component, only the newest self-signature is “in effect,” and older signatures are “shadowed.” For each certificate, there is at most one “active” direct key signature, for each User ID at most one active self-certification and for each subkey exactly one subkey binding.

23.4. Complexity of the packet format¶

OpenPGP certificates can contain complex preference settings. Additionally, the OpenPGP packet format allows a lot of flexibility when storing certificates in TPK format.

User ID packets, for example, do not have a fixed position in a TPK. This means an attacker (or an implementation-internal certificate canonicalization procedure) can change the order in which User IDs appear in the certificate’s packet sequence.

As a concrete example, consider a certificate with multiple User IDs, all marked as primary. Or similarly, a certificate with multiple User IDs of which none is marked as primary. Clients might apply different heuristics to figure out which User ID actually qualifies as the primary User ID here.

Such subtle changes to the representation of a certificate can lead to different preference settings being deduced, by different OpenPGP implementations.